Notes on Editing the X16 Font: HERE

This article is from September 2023.

Wintel = Windows and Intel “x86” (or compatible) processors

This guide will not cover basic OS skills such as creating folders, opening the command console, and navigating the file system from the command line. You will need to be somewhat familiar with these basic concepts first. This is focused as a quick guide on setting up and using cc65 to target the X16 platform.

Some desktop tools I use are:

- notepad++ (code editor, syntax highlight)

- FileLocator (aka AgentRansack) (file search, since Windows built-in search is hopeless)

- HxD64 (hex editor)

- BeyondCompare (many uses, but can compare .s files to monitor what the assembler is doing across builds)

Introduction and Starting the Emulator

I still use the old MS-DOS style black console window (CMD.EXE), not the fancy PowerShell stuff. I also almost never use the MyDocuments stuff (at least, if it is entirely “my computers”).

While this is not an “OS guide” there are a few file-system nuances to be aware of:

In Windows/DOS, each drive has its own CWD (current working directory). That means, if you type “cd f:\x16” then the CWD of the F: drive is set to \x16. You still have to actually go to the F: drive (if not the current drive already) to make it the actual current working folder.

NOTE: While a little advanced, you might consider using the Windows Disk Manager to create a “Virtual Hard Drive” to scope all your X16 related development to a single drive (which you can then “take with you” to other systems, like a laptop vs. desktop).

When you start the X16 emulator, your current folder will act as the SD-card content by default. You cannot “cd ..” up from this root folder, even if on the physical drive you started the emulator from is in a sub-folder. You can override this with the -fsroot (fs = file system) or -startin command line arguments, but I just stick to running the emulator from where I want the SD-card content to be. I make sub-folders for each SD-card (like an “sd” working files/folder, then a folder for the standard as-included SD-card content).

Here is an example of one way to startup the emulator:

Note that the emulator does not start in its own process, so the console window is not available when the emulator is running. If you need to get around that, use the “start” command (i.e. “start ..\x16emu.exe“). This is useful so you can then actively manipulate files/folders without having to close the emulator (but sometimes the emulator might “lock” a file if it is OPEN’d using a file handler).

Preparing the cc65 Development Folders

Obtain cc65 from here: https://github.com/cc65/cc65

Note on the right side of the web page is “Releases“, click on that and find a release V2.19 on or after May 2020. If of interest, to also get libsrc (the implementation of how cc65 handles certain things for the cc65 target), you can clone the entire cc65 repo (or just download the ZIP in the green drop down of the main cc65 github page).

When you “install” cc65 (download and decompress to a folder), an easy way to start is to just create a sub-folder for your project in that same folder. It is generally not a good practice to do this (i.e. your project content should be isolated from whatever development tool you happen to be using– so you can update versions of tool without risking losing your project files), but for starters this can make dealing with build paths easier.

Here is an example of a set of projects placed directly in the cc65 root folder. Once you get more familiar with the workflow (or add the cc65 binaries to the path), it is better to move these project folders outside of the cc65 directory hierarchy.

Now with two console windows and the emulator running, I can just ALT-TAB between what I need to do next. If I need to restart the emulator, then ALT-TAB to the “emulator console” and CTRL-C (or just up-arrow and ENTER to restart it; or use CTRL+ALT+R to reset the emulator). If I need to adjust code, then go to the project sub-folder (“cd” change directory commands) and use notepad++ to modify the necessary source.

Within the C project sub-folder, I create two folders for “include” and “source.” Being C source code, this is just “best practice” to keep interface (.h) files separated from source code (.c) files. It takes some experience to understand why – one reason is for cross-platform support, the .h files may remain the same but then different .c source implementation files used for each platform being ported to (such as main_x16.c versus main_a2.c for Apple ][ versus main_c64.c for C64 version, etc.).

Going Through the Motions: Compiling and Running

Within the source folder, I create two batch files: go_main_x16.bat and go_update.bat. The go_main_x16.bat script is used to compile the current project. So when I need to re-compile, I just ALT-TAB to my “compiler console”, mash UP ARROW, and ENTER. Then go_update.bat copies the “executable” (generated .PRG, if the compile was successful) to the emulator SD sub-folder I’m working with. To run the update script, ALT-TAB to the “emulator console”, CTRL-C, UP ARROW, and ENTER (to launch the emulator set to load and run the .PRG I’m working with).

With experience, you’ll realize to run the update script after compiling, you can just mash the DOWN ARROW and ENTER. Be sure to examine the compiler output to make sure it actually did compile correctly.

I put these support scripts right in the source folder and maintain as needed. But you could put them in a \script folders and do something like “..\scripts\go_main.bat”. Understanding “current working directory” and relative paths is another valuable (that is: batch scripts operate from the CWD you ran the script from, not relative to where the script file is located).

If you want to use other tools to edit or manipulate the files in the folder, use “start .” (start and “dot” or period) command to open the current folder in an Explorer Window. Obviously, you can set those tools to be in the environment path and all that, though I generally don’t bother (because as I migrate across systems to do my development, I try to avoid being dependent on a particular environment setup). Just use “start .” then type first few letters of the filename to highlight it, hit Context menu key, select desired tool (like “notepad++”). Hardly need to ever touch the mouse.

Below is sample content of the go_main_x16.bat file.

set CC65PATHBINROOT=F:\X16\cc65-snapshot-win32\bin

set CC65PATHINCROOT=F:\X16\cc65-snapshot-win32\include

REM COMPILER to assembly

rem set OPTIMIZE=

set OPTIMIZE=-O -Oi -Or -Os

%CC65PATHBINROOT%\cc65 %OPTIMIZE% --target cx16 --include-dir ..\include --include-dir %CC65PATHINCROOT% main.c

REM repeat the above for each .c file you need

REM ASSEMBLER to object code

%CC65PATHBINROOT%\ca65 --target cx16 main.s

REM repeat the above for each .s file you generate

REM LINKER to executable

%CC65PATHBINROOT%\ld65 --target cx16 --obj main.o --lib ..\lib\cx16.lib -o main_cx16.out

REM if multiple .o files, just list them after the --obj argument

Describing this script: First set variables to the root of your cc65 installation (I do one for the compiler executables and a separate for the include folder of the Standard Library). Doing this helps as you scale up to more files involved in the project and helps make your source code folder be “more portable” and not locked to being placed in the compiler tool folder.

At some point you may want to disable optimization (such as when you want to compare .s outputs to see exactly what the optimization is doing). But typically, you’d just leave all the optimization options on (the -O options).

COMPILE: Then you need a call to cc65 for each “.c” needed in your project. Typically, I always put the main() function in a main.c file. You can do a for-loop in the script, but I generally just list each .c for a modest sized project in case I want to disable or comment out just one of them later (especially if a portion of code is “done” and I don’t need to re-compile it for a while).

ASSEMBLE: Next you need to assemble your resulting compiled file using ca65. From the above step, each .c becomes a .s file that is the assembly language representation of the C-code. Now the assemble process here parses the .s files to produce .o (object code) files, that is essentially raw machine code of the assembly code (with things like branch offset targets more formally computed and represented by the appropriate opcodes).

NOTE: When I’m analyzing performance (like when using the “register” keyword explicitly), I’ll copy the prior build .s to another filename. Then in the next build, use BeyondCompare to examine the new and old .s files.

LINK: The resulting .o file (or files) need to be linked together into an “executable.” In general, there can be a lot that goes into linking, depending on the ROM build and OS being targeted in more complex systems. The linker makes decision on which addresses the code should go at. There is a “cx16.cfg” file in the cc65 installation that is used to define which addresses are “blocked out” (reserved for system use, not application use) and how much stack space to reserve. There are a lot of intricacies here for linking, but in general all your .o files get packaged into a single .PRG that represents the “executable” form of your program.

A .PRG file is not quite the same as a .EXE file. For one thing, even to do this day, you will see that .EXE files start with “MZ” (initials of one of the Microsoft employees who came up with the format). .COM files were “real mode” straight up 16-bit address space limited. .EXE files allowed for larger programs that could function across multiple memory segments. That is, .COM come from CP/M days and would be loaded into 0x0100 (of any segment) and just run it (with no real operating system requirements, as long as you had a way to get the .COM file contents into RAM). .EXE files depend on some coordination of the operating system for some ground rules on how it is loaded into memory and start running (and things like passing command line arguments). A .PRG is more like a .COM file (where .PRG is program and .COM meant “command“, not to be confused with Common Object Model or .com websites).

When a binary PRG file is loaded via the X16 BASIC LOAD command, it has some “rules” on where the code in that PRG is loaded into so that initial execution can be started. These rules can vary depending on some argument values passed to the LOAD command, which can get a little confusing since a PRG file (or any file given to the LOAD command) could also contain a “tokenized BASIC program.” This isn’t a guide about BASIC, but this is an area where cc65 is especially suited to supporting the X16 platform: the generated PRG will contain a small header that “knows how to load itself” when you RUN it after a LOAD command.

NOTE: “cx16.lib” is cc65’s implementation of the C-standard library, as needed for the X16 platform. The C-standard library provides a lot of utility to quickly help test out some concepts, but in general a goal is to minimize usage and dependency on that standard library (especially since it quickly consumes up a lot of code space). This is not saying there is anything wrong with the C-standard library, just it contains a lot of features that either consume code space or cost extra runtime that you may not need. That said, even if do nothing with the C-Standard Library, linking in cx16.lib is still necessary for some minimum support needs (like some rules on how stack allocation is performed or multiplying 16-bit values).

Be aware that conio.h is not really “standard C library” content. It is “Console I/O” support routines for writing content to the console screen (columns/rows), moving the cursor, or setting colors. Most late 1970s platforms will have something like “conio.h” (but C was also for “embedded systems” that had no screen console at all, so support for that hardware wasn’t considered as essential for the “standard library”).

Once the compiler, assembler, and link steps are all completed I then use the UPDATE script to copy the built executable over to the emulator working folder. After doing this at least once, thereafter I just DOWN ARROW and ENTER, then ALT-TAB over to the emulator console and restart it (with that -prg specified in the command line argument; just UP ARROW and ENTER).

copy main_cx16.out ..\..\..\x16emu_win64-r43\MAIN_CX16.PRGSo, a typical “update session” might look like this:

Then flip to the “other” console window, and invoke the emulator like this:

Sometimes I won’t use -run, just depending on what I’m testing. Sometimes I may need to prepare the screen size or some aspect of the setup before running the program.

NOTE: When using the emulator -prg command line argument, it is very accommodating on loading the specified filename. But the real system is a bit more picky since users will have to use the BASIC LOAD command. It is best to go ahead and specify your PRG output using UPPERCASE letters and (if needed) use DASHES instead of UNDERSCORE to separate words in your filename. Filenames containing lower case letters and underscore symbol end up with more difficult to type characters when translated over to the X16 BASIC system. So it just makes life easier on end-users to just keep your filenames uppercase and no underscores. The .PRG extension is also optional, but as a convention for a compiled program, the .PRG has become a nice standard.

Here is an example main.c to start with:

#include <stdlib.h> //< Used for itoa, srand and exit

#include <stdio.h> //< printf and fopen

#include <conio.h> //< cgetc, gotoxy

#include <cx16.h> //< videomode, etc.

void main(void)

{

// in "classic C" declarations must be first...

unsigned int i;

unsigned char ch;

ch = cgetc();

printf("you pressed [%c]\n", ch);

for (i = 250; i < 300; ++i) {

printf("%u ", i);

}

}

And there you go: the sample program is now running in the emulator.

A couple important things to note:

- cc65 startup runtime (cx16.lib) forces the program into a different character set mode than the X16 default. No one knows why this is; the X16 default startup mode is UPPER/GRX mode and character set. After the program ends, you can press SHIFT+LEFT ALT to swap the system between these character sets. But this also indicates the cx16.lib probably contains the actual _main entry point of the program, does some initialization (such as obtaining command line arguments), then calls your program main().

- When a cc65 built program ends, you cannot RUN it again right away. We haven’t yet resolved why this is. It is most likely due to some ROM changes between when the X16 project started and when cc65 initially added support for the X16 target. This may get ironed out eventually, but in the mean time if you just LOAD the program again, then you RUN it again. Or alternatively, reset the system and then LOAD again.

Transferring PRG to the Hardware

You will need an SD-card USB reader for your system. I use this “SmartQ C368 Pro USB 3.0 Multi-Card Reader” model, under $20 and haven’t had any troubles with it. Copy your PRG file to the SD-card, then migrate the SD-card over to the X16.

From BASIC, LOAD your PRG file (e.g. LOAD “MAIN TEST.PRG”). If you do a listing, it should say something like “531 SYS2061” which is a SYSTEM CALL to address $80D (hex, or 2061 decimal). The cx16.cfg has a STARTADDRESS of $0801 (by default), but a brief BASIC header is used to kickoff starting the actual program binary (which ends up starting at $080D).

VTERM running on real hardware.

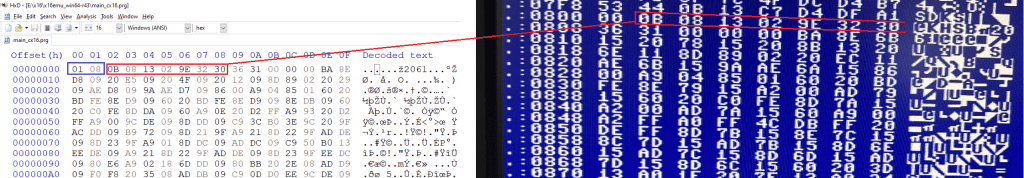

Notice the same content from the PRG file ends up at the address listed in the first two bytes of the PRG (01 08, reversed to $0801).

Next Steps

Here are some C code tips that I use with cc65 and the X16…

I’m not 100% sure if these pragma’s help in every situation, but something to be aware of…

// The following are optimizations intended for the cc65 compiler environment

#pragma inline-stdfuncs (on)

#pragma static-locals (on)

#pragma register-vars (on)You can include “peekpoke.h” but I generally start defining my own core_cx16.h to hold key things I use:

// peekpoke.h

#define POKE(addr,val) (*(unsigned char*) (addr) = (val))

#define POKEW(addr,val) (*(unsigned*) (addr) = (val))

#define PEEK(addr) (*(unsigned char*) (addr))

#define PEEKW(addr) (*(unsigned*) (addr))X16 foreground and background color codes (a version of these come with cc65 cx16.h, though I generally avoid that header).

#define CX16_BG_BLACK 0x00

#define CX16_BG_WHITE 0x10

#define CX16_BG_RED 0x20

#define CX16_BG_CYAN 0x30

#define CX16_BG_PURPLE 0x40

#define CX16_BG_GREEN 0x50

#define CX16_BG_BLUE 0x60

#define CX16_BG_YELLOW 0x70

#define CX16_BG_ORANGE 0x80

#define CX16_BG_BROWN 0x90

#define CX16_BG_LT_RED 0xA0

#define CX16_BG_DK_GRAY 0xB0

#define CX16_BG_LT_GRAY 0xC0

#define CX16_BG_LT_GREEN 0xD0

#define CX16_BG_LT_BLUE 0xE0

#define CX16_BG_MED_GRAY 0xF0

#define CX16_FG_BLACK 0x00

#define CX16_FG_WHITE 0x01

#define CX16_FG_RED 0x02

#define CX16_FG_CYAN 0x03

#define CX16_FG_PURPLE 0x04

#define CX16_FG_GREEN 0x05

#define CX16_FG_BLUE 0x06

#define CX16_FG_YELLOW 0x07

#define CX16_FG_ORANGE 0x08

#define CX16_FG_BROWN 0x09

#define CX16_FG_LT_RED 0x0A

#define CX16_FG_DK_GRAY 0x0B

#define CX16_FG_LT_GRAY 0x0C

#define CX16_FG_LT_GREEN 0x0D

#define CX16_FG_LT_BLUE 0x0E

#define CX16_FG_MED_GRAY 0x0F

#define CX16_KEY_MOD_SHIFT 1

#define CX16_KEY_MOD_ALT 2

#define CX16_KEY_MOD_CTRL 4

#define CX16_KEY_MOD_CAPS 16 // caps lock onAll the screen text modes will start their rows at these addresses in VRAM (which note they are spaced out by 256 bytes). These aren’t really addresses per se, but the next example will clarify how these are used:

static unsigned char cx16_screen_row_offset[] = {

0xB0,0xB1,0xB2,0xB3,0xB4,0xB5,0xB6,0xB7,0xB8,0xB9,

0xBA,0xBB,0xBC,0xBD,0xBE,0xBF,0xC0,0xC1,0xC2,0xC3,

0xC4,0xC5,0xC6,0xC7,0xC8,0xC9,0xCA,0xCB,0xCC,0xCD,

0xCE,0xCF,0xD0,0xD1,0xD2,0xD3,0xD4,0xD5,0xD6,0xD7,

0xD8,0xD9,0xDA,0xDB,0xDC,0xDD,0xDE,0xDF,0xE0,0xE1,

0xE2,0xE3,0xE4,0xE5,0xE6,0xE7,0xE8,0xE9,0xEA,0xEB

};Use of addresses tied to the VERA hardware to interact with VRAM:

#define CX16_WRITE_XY(x, y, disp_out) \

POKE(0x9F20, x << 1); \

POKE(0x9F21, cx16_screen_row_offset[y] ); \

POKE(0x9F22, 0x21); \

POKE(0x9F23, disp_out);

#define CX16_WRITE_X(x, disp_out) \

POKE(0x9F20, x << 1); \

POKE(0x9F22, 0x21); \

POKE(0x9F23, disp_out);

#define CX16_WRITE_Y(y, disp_out) \

POKE(0x9F21, cx16_screen_row_offset[y] ); \

POKE(0x9F22, 0x21); \

POKE(0x9F23, disp_out);

#define CX16_WRITE(disp_out) \

POKE(0x9F22, 0x21); \

POKE(0x9F23, disp_out);

// col_out = <background> | <foreground>

// example: CX16_COLOR_XY(10, 5, CX16_BG_BLACK | CX16_FG_WHITE);

#define CX16_COLOR_XY(x, y, col_out) \

POKE(0x9F20, (x << 1)+1); \

POKE(0x9F21, cx16_screen_row_offset[y] ); \

POKE(0x9F22, 0x21); \

POKE(0x9F23, col_out);

#define CX16_COLOR_X(x, col_out) \

POKE(0x9F20, (x << 1)+1); \

POKE(0x9F22, 0x21); \

POKE(0x9F23, col_out);

#define CX16_COLOR_Y(y, col_out) \

POKE(0x9F21, cx16_screen_row_offset[y] ); \

POKE(0x9F22, 0x21); \

POKE(0x9F23, col_out);

#define CX16_COLOR(col_out) \

POKE(0x9F22, 0x21); \

POKE(0x9F23, col_out);

#define READ_CHAR(x,y,z) \

POKE(0x9F20, x << 1); \

POKE(0x9F21, cx16_cx16_screen_row_offset[y] ); \

POKE(0x9F22, 0x21); \

PEEK(0x9F23, z);Example of keyboard query, screen mode changes, and utility macros. This is using the inline assembly features of cc65:

#define GET_CX16_KEY(ch) \

__asm__("jsr $ffe4"); \

__asm__("sta %v", ch);

#define ENABLE_SCREEN_MODE_3 \

__asm__("lda #$03"); \

__asm__("clc"); \

__asm__("jsr $ff5f");

#define CLRSCR \

__asm__("lda #$93"); \

__asm__("jsr $ffd2");

unsigned char check_kbd_modifiers()

{

static unsigned char modifiers;

__asm__("jsr $fec0"); // kbdbuf_get_modifiers

__asm__("sta %v", modifiers);

return modifiers;

}

// BIT-MASK SUPPORT (0-7 OFFSET BASED)

#define SET_BIT(n, k) n = (n | (1 << (k)))

#define CLEAR_BIT(n, k) n = (n & (~(1 << (k))))

#define TOGGLE_BIT(n, k) n = (n ^ (1 << (k)))

#define IS_BIT_ON(n, k) ((n & (1 << (k))) ? TRUE : FALSE)

// Using these MASK macros is even better, no shifting.

#define MASK_HIGH_BIT 0x80 // 1000 0000

#define IS_MASK_ON(mask, bit) \

((mask & bit) == bit)

#define IS_MASK_OFF(mask, bit) \

((mask & bit) != bit)

#define SET_MASK(mask, bit) \

(mask = (mask | bit))

#define CLEAR_MASK(mask, bit) \

(mask = (mask & ~bit))The following is what I use to get the jiffies timer:

typedef struct {

unsigned char second_jiffies; // 4.25sec * 255 = 1083.75 seconds (about 18.0625 minutes)

unsigned char first_jiffies; // 1/60sec * 255 = 4.25 seconds

unsigned char jiffies;

} CX16_clock_type;

extern CX16_clock_type cx16_clock;

void cx16_init_clock();

void cx16_update_clock();Then in a .c you define the implementation of cx16_init_clock and cx16_update_clock as follows (which is good practice now at expanding your cc65 project to compile and link together multiple .c files; although not recommended, you could toss these implementations in your main.c).

CX16_clock_type cx16_clock;

void cx16_init_clock()

{

__asm__("LDA #0"); // jiffies

__asm__("LDX #$FF"); // group1

__asm__("LDY #$FF"); // group2

__asm__("JSR $FFDB");

}

void cx16_update_clock()

{

static unsigned char reg_a;

static unsigned char reg_x;

static unsigned char reg_y;

__asm__("JSR $FFDE");

__asm__("STA %v", reg_a);

__asm__("STX %v", reg_x);

__asm__("STY %v", reg_y);

cx16_clock.jiffies = reg_a;

cx16_clock.first_jiffies = reg_x;

cx16_clock.second_jiffies = reg_y;

}

Ok, that’s a lot of macros and inline assembly. Why not just do assembly then?

Great question! The answer is C lets you define struct, more easily convey controls (for and while loops), define functions and pass arguments. You can also use malloc and free (of up to about 25KB), and also use pointers to navigate through arrays of structs.

Pure assembly is nice, but you can sometimes “paint yourself into a corner.” This means you write a bunch of code and then get a new idea, but can’t easily incorporate it into your assembly code because of some earlier assumptions. C code tends to be a little more “malleable.” As an example, if you want to add some data to a struct, you just do so and the compiled code will adjust accordingly. In assembly, this could mean a lot of jumps and offsets need to be manually updated – where difficult to track down bugs come about when just one of those gets overlooked.

That said, a well written assembly program is like a piece of art in its precision.

File I/O

A warning about file I/O in cc65 and the X16…

FILE, fopen/fclose, all do work. But the main limitation is that the fopen filename string is limited to 16 characters. That’s including both the path and filename. This effectively means that long filenames are not supported through those interfaces.

But, there is a workaround! When you specify “-target cx16” on the command line for cc65 (and ca65), that enables two macros: __CX16__ and __CBM__ . When target.h is processed (like when you bring in conio.h), that brings in cbm.h This in turn brings in may “cbm_xxx” interfaces, like “cbm_open” for opening files, along with cbm_read and cbm_close. In the cbm.h are comments to better described these functions. But they effectively wrap the equivalent BASIC commands of the same names (which in turn wrap various KERNAL calls). These at least allow use of long paths and filenames.